Alan Jackson’s Closing Argument: Strong Points, Shaky Delivery

When defense attorney Alan Jackson stood to deliver his closing argument in the Karen Read trial, expectations were sky-high. Jackson has a reputation as a legendary trial lawyer, but his performance was oddly rigid, as he remained glued to the podium and read from a 3-ring binder like a flustered college professor mid-tenure review.

Compared to Hank Brennan’s cinematic courtroom performance—pacing the floor, commanding attention like a Broadway lead—Jackson’s energy felt more Sunday sermon than courtroom drama. And yet, despite the delivery, Jackson’s substance was stacked with serious firepower.

Staring Down Injustice: The Emotional Frame

Jackson opened not with evidence, but with a call to arms. He positioned the jury as the final line of defense against a broken system, imploring them to “stare directly at injustice and say, ‘Not here, not now, not on our watch.’” He painted the prosecution as agents of institutional failure—a rigged system that chews up the innocent.

This wasn’t just about Karen Read, he argued; this was about the soul of justice. It was emotional, rhetorical, and designed to infuse the jury with moral purpose. Think Atticus Finch meets Network’s “I’m mad as hell” monologue.

Reasonable Doubt: A Constitutional Wall

Jackson then drilled deep into the concept of reasonable doubt, reminding the jury that “maybe,” “likely,” or even “very likely” still means not guilty. He delivered a legal lecture disguised as a crusade, emphasizing that unless the Commonwealth proved Read’s guilt “to a moral certainty,” the law requires acquittal.

It was an effective way to anchor the defense in principle—but let’s be honest, it also felt like being told 16 different ways to fold a fitted sheet. Thorough? Yes. Dynamic? Not so much.

The Central Theme: “There Was No Collision”

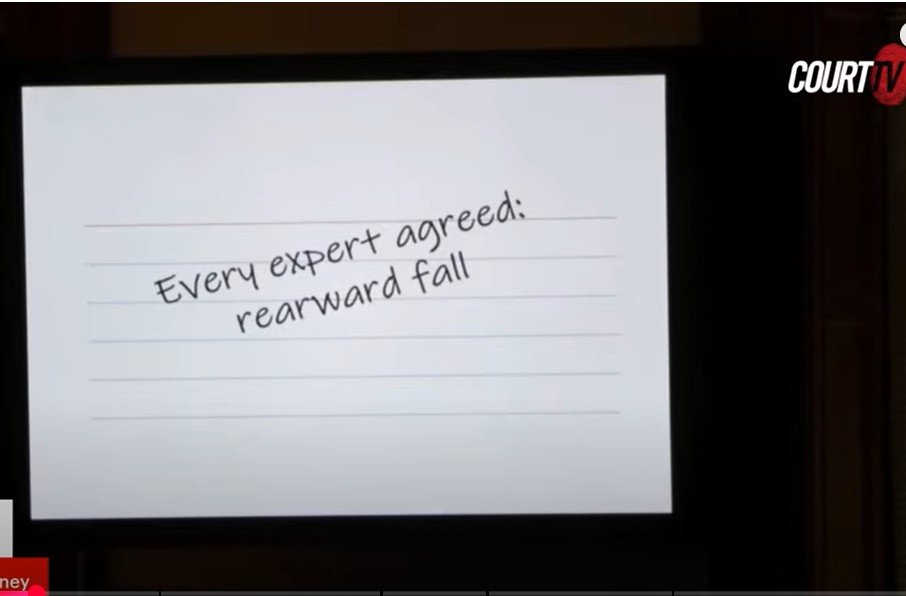

Jackson’s mantra throughout: “There was no collision.” He repeated it like a gospel refrain. He claimed the Commonwealth failed to prove that John O’Keefe was struck by Karen Read’s SUV because the evidence told a different story.

There were no bruises, no fractures, no internal trauma typical of being hit by a 6,000-lb vehicle.

John’s arm, according to Jackson and a lineup of defense experts, was pristine—save for what they insisted were dog bites. His punchline? “You can manipulate a tail light fragment. You can’t manipulate a bruise.”

.

The Science: Team Defense vs. Team Theatrics

Jackson flexed the defense’s science muscle hard. He cited multiple independent experts who performed physical testing—field tests, lab tests, ARCCA crash reconstruction—all showing that Read’s SUV damage wasn’t consistent with hitting a human arm.

Meanwhile, he mocked the prosecution’s $400,000 “blue paint kindergarten project,” ridiculing their expert (Jud Welcher) for showing the jury how tall John O’Keefe was, but admitting he lacked enough evidence to reconstruct the crash.

Jackson’s sarcasm was biting: “If there’s not enough evidence to know what happened… that’s called reasonable doubt.”

Attacking the Investigation: Proctor, Proctor, Proctor

Jackson didn’t just poke holes in the investigation—he took a wrecking ball to it. Lead investigator Michael Proctor was depicted as biased, unethical, unprofessional, and ultimately fired for cause. His infamous texts—calling Karen a “whack job,” joking about her anatomy, and declaring “zero chance she skates” hours into the case—became Exhibit A in the defense’s narrative of systemic misconduct.

Jackson emphasized that Proctor handled every key piece of evidence, including the now-infamous shards of taillight plastic. If you don’t trust the man, Jackson argued, how can you trust the chain of custody?

The Dog Did It: Chloe Takes Center Stage

In what might be the most unconventional defense strategy since “the glove didn’t fit,” Jackson introduced the real culprit: Chloe, Brian Albert’s German Shepherd. He argued that John’s arm wounds were clearly dog bites—not glass cuts—and that Chloe conveniently disappeared the morning after the incident. No officers reported seeing her. She was later given away.

Jackson’s subtext? The dog didn’t just bite John—she bit the Commonwealth’s entire case in half.

Sub Heading

The House That Wasn’t Searched

Jackson hammered investigators for not searching the Albert home, despite a dead man being found on their front lawn. No warrant. No photos. No forensics. Not even a walkthrough. “They didn’t open the garage door,” he scoffed, repeating the phrase like a damning indictment. And he posed the haunting question: If it had been anyone else’s house—not a Boston cop’s—would police have torn it apart looking for evidence?

Witness Credibility: Lies, Perjury, and “False Memories”

Jackson tore into the credibility of key prosecution witnesses. Jennifer McCabe? Lied about her Google search. Kerri Roberts? Admitted to perjury. Officer Kelly Dever? Gave detailed testimony about seeing Brian Higgins in the Sallyport, then suddenly backpedaled after a cozy chat with the police commissioner—calling her own statement a “false memory.” Jackson held these inconsistencies up like trophies, suggesting that the Commonwealth’s case was built on sand and propped up by coerced or manipulated witnesses.

The Data Problem: The Prosecution’s Timeline Collapses

Using the prosecution’s own tech expert, Jackson blew a crater in their timeline. If John was struck at 12:31:38 a.m., why was he still walking, using his phone, and logging steps after that time? Their own digital trail betrayed them. Even their star data expert Shanon Burgess “came up with a brand-new story mid-trial,” Jackson said, dripping with disdain. And if he couldn’t stick to a single version, how could the jury convict?

And sometimes, in the courtroom, knowing enough is everything.

Performance Notes: When Style and Substance Clash

Despite the strength of Jackson’s argument, the performance left something to be desired. While Hank Brennan glided around the courtroom like a director guiding his cast, Jackson barked at the jury like a prosecuting prophet. His tone was often angry, at times scolding, and rarely personal. He was more John the Baptist than Atticus Finch. It’s not that his arguments were weak—on the contrary, they were methodical and often compelling. But the tone may have made some jurors recoil instead of lean in.

Practicing Fighting…?

RIGHT?! That whole “sparring in a bar = murder prep” moment is such a leap, it practically needs a cape and a Marvel franchise.

Like—two guys goofing off with pretend jabs after a few drinks is not a covert dry run for homicide. It’s not Fight Club, it’s frat night. The defense is over here acting like Brian Higgins and Brian Albert watched Rocky IV together and then said, “Now, let’s use this technique on a Boston cop in a snowstorm with a German shepherd backup.”

It’s such a desperate attempt to make mundane male behavior into premeditated menace. And while Jackson’s delivery was dead serious, the content was practically camp. You could just feel him trying to thread that moment into his “Higgins was jealous, brooding, and violent” narrative—but it landed like, okay… and?

Frankly, that’s the problem with some of the defense theory—it’s like putting together a jigsaw puzzle from four different boxes, then yelling at the jury for not seeing the picture.

Final Verdict: A Strong Case Delivered with a Heavy Hand

Alan Jackson’s closing was a masterclass in reasonable doubt and scientific storytelling—delivered, unfortunately, with the warmth of a DMV announcement. He raised serious, specific, and persuasive points. If even one juror believed the dog did it, or found Proctor’s behavior unforgivable, that’s a hung jury. If more believed it, Karen Read walks free with only a misdemeanor drinking and driving charge and likely probation.

But delivery matters. While some facts may favor the defense, Jackson’s confrontational tone may have alienated the very jurors he needed to persuade. Sometimes, even when you’ve built a strong house—if you scream at the people inside, they might not want to stay.

Related Articles

Related

Hold On a Minute: What Media Is Saying About Nick Reiner

There has been exactly two real developments in the Nick Reiner case: a change in attorneys and a new arraignment date set. That’s it. No evidence dump.No discovery.No probable cause affidavit released.No forensic details confirmed on the record. And yet somehow —...

Nick Reiner Hearing: Defense Reset, Media Spin, and What Actually Happened

The January hearing in the Nick Reiner case produced more media noise than legal substance — and much of that noise was wrong. While some outlets rushed to frame the day as a dramatic turn toward an insanity defense, the courtroom record tells a more procedural,...

Nick Reiner: Schizophrenia or Narrative Shift?

In the earliest days of a high-profile criminal case involving son of Rob and Michele Reiner, Nick, narratives often solidify before facts are tested. Once that happens, speculation hardens into assumption—and assumption begins to masquerade as inevitability. That is...