Brian Walshe Trial Day 10 – Jury Instructions

With evidence closed and emotions set aside, jurors are instructed on murder, intent, and premeditation—before the final arguments send the case into deliberations.

The Law Takes the Wheel

Day 10 marked the transition from evidence to decision-making. With testimony complete, the court finalized jury instructions outside the presence of the jury, addressed minor but important edits, and then instructed jurors on the law governing the single charge they must decide. Closing arguments followed, after which the case moved toward deliberations.

This article focuses on what the jury is actually deciding — and what the Commonwealth must prove to secure a conviction.

The Charge Before the Jury

There is one indictment in this case:

Murder (with two possible degrees)

The jury must first decide guilt or innocence. If they find the defendant guilty of murder, they must then determine the degree.

Verdict Options on the Jury Form

The jury will deliberate among three outcomes:

☐ Not Guilty

☐ Guilty of Murder in the First Degree (Deliberate Premeditation)

☐ Guilty of Murder in the Second Degree

The judge instructed jurors that if they find guilt, they must return a verdict on the most serious offense proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

What the Commonwealth Must Prove

Murder in the First Degree

Theory: Deliberate Premeditation

To convict on first-degree murder, the jury must be unanimous and find that the Commonwealth proved all three elements beyond a reasonable doubt:

Causation

The defendant caused the death of Ana Walshe.Intent to Kill

The defendant consciously and purposefully intended to cause her death.Deliberate Premeditation

The defendant decided to kill after a period of reflection.

Importantly, the judge emphasized:

Premeditation does not require a long time, It can occur in seconds. What matters is the sequence of thought:

Consideration → decision → action

Not a purely impulsive act

This instruction squarely frames the Commonwealth’s theory — and the defense’s primary target.

Murder in the Second Degree

If the jury does not unanimously find deliberate premeditation, they must still consider second-degree murder.

The Commonwealth must prove:

Causation

The defendant caused the death of Ana Walshe.

One of three intent prongs (only one is required):

Intent to kill, or

Intent to cause grievous bodily harm, or

Intent to commit an act that a reasonable person would know created a plain and strong likelihood of death

This third prong significantly lowers the Commonwealth’s burden compared to first-degree murder and provides a clear off-ramp for jurors struggling with premeditation but convinced the killing was intentional or recklessly deadly.

Instruction Edits That Matter (Without Jury Present)

Several edits are worth noting, not because they change the law, but because they tighten the presentation:

“Use of a dangerous weapon” language removed

This avoids importing an element that was not charged.

Graphic photo instruction trimmed

The judge removed language deemed irrelevant — a subtle signal to jurors to focus on proof, not emotional impact.

Evidence instruction streamlined

Stipulations were folded directly into the definition of evidence, reinforcing that jurors may consider agreed-upon facts the same as testimony.

Tools sent to deliberations — safely

The court discussed how physical tools would be secured for jury review, confirming they remain part of deliberations but without dramatization.

None of these changes favors one side overtly, but collectively they reinforce a controlled, law-focused deliberation environment.

Why This Framing Matters Going Into Closings

By breaking the instructions into two phases — charge-specific first, then general law later — the judge ensured jurors heard the elements of murder before closing arguments, anchoring how they would listen to counsel.

That sequencing matters: The defense closes first. The Commonwealth closes last. Jurors already know exactly what must be proven when arguments begin. This structure subtly benefits whichever side can most clearly map evidence to elements — or expose gaps between the two.

Where This Sets Up the Closings

With the law now fixed, the closings are not about speculation or narrative flourish. They are about intent, premeditation vs. impulsivity, and whether the evidence supports reflection before action.

The jury has been told precisely what questions they must answer — and in what order.

Final Jury Instructions: What the Jury Was Told to Remember

Brian Walshe - Reality Sets in Immediately After the CW Closing

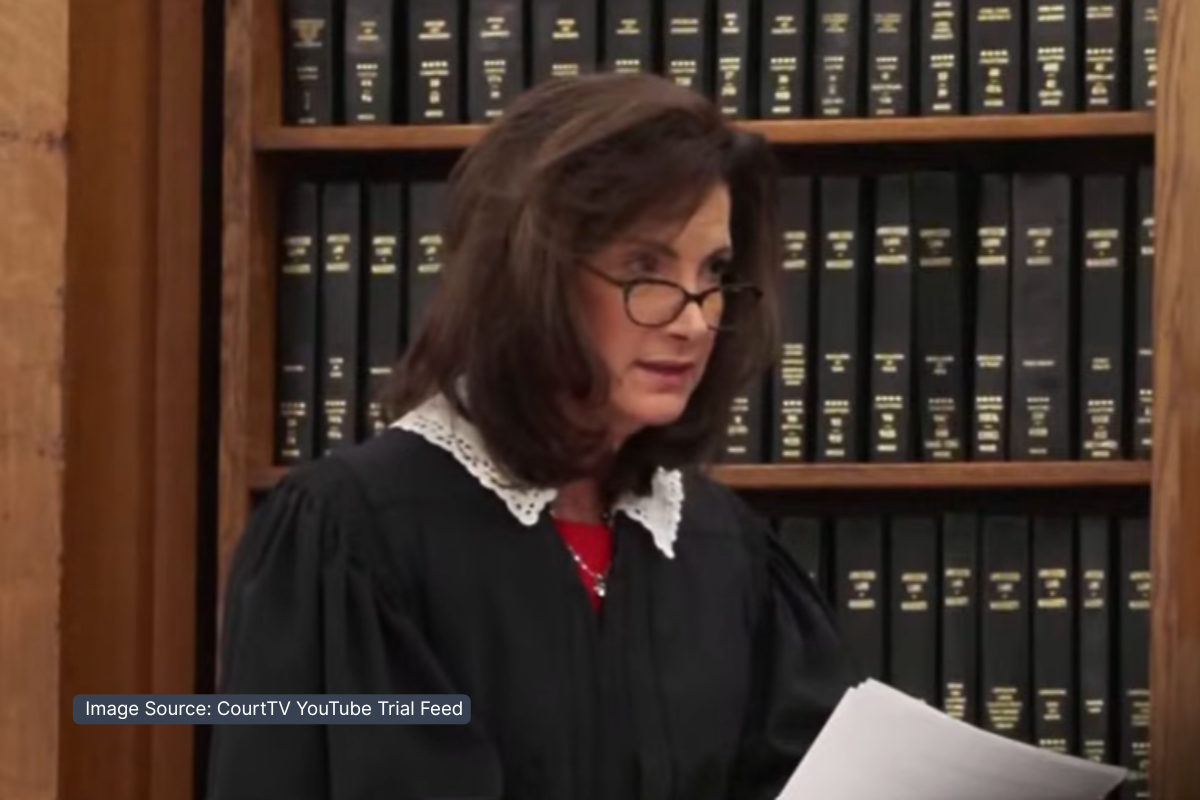

In the final phase of instructions, Judge Freniere shifted from defining the legal elements of murder to explaining how jurors must deliberate. The emphasis was not on emotion, punishment, or speculation, but on discipline: fairness, neutrality, and strict adherence to evidence and law.

The judge repeatedly reminded jurors that their role was not to solve a mystery or express moral outrage, but to determine whether the Commonwealth met its burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt—and nothing more.

Key Instructions the Jury Will Carry Into Deliberations

⚖️ No Emotions. No Prejudice. No Sympathy.

This was one of the clearest and most forceful themes of the instructions:

“Do not let your emotions, any kind of prejudice, or your personal likes or dislikes influence you in any way.”

“Do not be influenced by the nature of the charge or the possible consequences of your verdict.”

“You can’t base your decision on sympathy, anger, passion, or prejudice or pity for or against either side.”

The judge explicitly acknowledged that the evidence could provoke strong emotional reactions—but instructed jurors that those reactions must be set aside.

🧠 Graphic Evidence Is Not a Shortcut to Guilt

Judge Freniere directly addressed the disturbing nature of some evidence:

“Some of these photographs may be unpleasant or graphic. Your verdict must not in any way be influenced by that fact.”

“The defendant is entitled to a verdict based solely on the evidence and not one based on pity or sympathy for the deceased.”

This instruction sharply limits the persuasive power of post-mortem evidence and reinforces the requirement that proof of murder must stand independently of emotional response.

🔍 Evidence Means Evidence — Not Guesswork

The judge was unambiguous about what jurors may and may not consider:

“You must decide this case based only on the evidence presented at trial.”

“You may not base your verdict on guesswork, speculation, or suspicion.”

“Anything you have read, heard, or seen outside this courtroom is not evidence.”

This is particularly significant in a high-profile case with extensive media coverage.

🚫 The Defendant’s Silence Is Not Evidence

The court reinforced a core constitutional principle:

“Mr. Walsh did not testify. You may not hold that against him.”

“The fact that Mr. Walsh did not testify is not evidence. You may not consider it or even discuss it.”

This instruction removes any inference-based shortcut jurors might otherwise take.

🧑⚖️ You Decide Credibility — Even for Experts

Jurors were reminded that no witness is entitled to automatic belief:

“You can believe all, some, or none of a witness’s testimony.”

“Expert witnesses don’t decide cases — juries do.”

“You may reject expert testimony in whole or in part.”

This gives jurors wide discretion — but also responsibility — in weighing forensic and expert evidence.

🧭 Deliberate Carefully, Not Quickly

In a notable section on decision-making, Judge Freniere offered guidance that goes beyond boilerplate instructions:

“Slow down. Do not rush to a decision.”

“Consider not only the evidence that supports your conclusions, but also evidence that undermines them.”

“Ask yourself whether your decision would be different if the people involved were different.”

This language encourages self-awareness and bias-checking, a rare but impactful inclusion.

🔐 Deliberations Must Remain Private

Before sending jurors out, the judge stressed confidentiality:

“You must keep your deliberations secret.”

“Do not tell anyone — not even me — anything about your discussions or votes.”

“Any questions must come in writing, signed by the foreperson.”

Sending the Jury Out — and the First Question

After closing arguments, the jury was formally sent to deliberate. Later, they submitted one written question to the court (the content of which was addressed with counsel present). After receiving a response, jurors were instructed to continue deliberations and were eventually sent home for the evening.

The exchange underscored that deliberations were active, careful, and methodical — not perfunctory.

The Framework the Jury Must Follow

These final instructions form the guardrails of deliberations. They narrow the jury’s task to a single question:

Has the Commonwealth proved every required element beyond a reasonable doubt — without emotion, speculation, or external influence?

Everything that follows — including the verdict — must fit inside that frame.

Related Articles

Brian Walshe Trial Day 10 | Closing Arguments

As the Brian Walshe trial moved into its final phase, the closing arguments distilled weeks of testimony into two sharply different narratives. The Commonwealth urged jurors to view the evidence as proof of a calculated, premeditated murder followed by deliberate...

Brian Walshe Trial Implodes Mid-Stream: The Defense Walks Off the Stage

The Commonwealth closed its case on December 10 after presenting a dense stack of forensic evidence, digital breadcrumbs, and witness testimony. But the real story unfolded immediately afterward — in the small procedural moments that signaled the trial was about to...

Brian Walshe Trial Day 4 – Ana’s Affair: William Fastow Testimony

When the prosecution called William Fastow, Ana Walshe’s D.C. lover, they were clearly aiming to build a motive: a failing marriage, a wife emotionally checked out, a husband allegedly pushed to a breaking point. But by the time Fastow stepped off the stand, many...