A Timeline on Trial: DiSogra vs. the Digital Evidence

In a trial already saturated with technical debates and digital data drama, defense expert Matthew DiSogra took the stand to unpack the now-infamous 1162–2 reverse maneuver vehicle event in the Karen Read case. A specialist in accident reconstruction and infotainment system analysis, DiSogra reviewed the work of fellow prosecution experts Shanon Burgess and Dr. Welcher, offering his own interpretation of when — and possibly if — John O’Keefe’s phone locked in relation to the vehicle’s key event trigger.

What followed was a dense and occasionally dizzying dive into time stamps, clock drift, GPS coordinates, and sidebars galore. While DiSogra challenged several assumptions in the prosecution’s timeline, he struggled to clarify some of his own, leaving many courtroom observers asking: “Where’s the spreadsheet?”

Dissecting the Data: A New Expert Enters the Timeline Debate

🔧 Credentials and Purpose

Matthew DiSogra is an accident reconstruction expert from Delta V Forensic Engineering, specializing in vehicle data recorders and infotainment system data.

His role was to analyze previous expert reports (Shanon Burgess and Dr. Welcher) and clarify clock alignment and timing surrounding vehicle and phone events.

📊 Event Timing Analysis

DiSogra’s Focus was on TechStream Event 1162-2, which recorded vehicle data triggered by a strong acceleration in reverse right about the time John O’Keefe became incapacitated.

Trigger time: 12:31:38 AM

End of event: 12:31:43 AM

Phone lock: 12:32:09 AM

DiSogra emphasized that everything should be referenced from the trigger point, not the end time, and that misalignment leads to inaccurate conclusions.

🕵️ Clock Drift, Time Adjustments, and Variability

Key critique: Burgess and Welcher’s original reports used the end of the event as the reference point, which could make the phone lock time seem earlier than it was by up to 5 seconds.

DiSogra claimed that adjusting for known offsets (like clock drift or key-on lag) still results in the phone lock happening after the vehicle event.

There was a three-second lag noted when turning on the car (based on an exemplar vehicle), but Burgess did not apply it in his analysis. DiSogra did both with and without it, showing a wider time gap when applied.

📈 Report Versions and Revisions

January vs. May reports: The January Burgess report used phone calls for clock alignment. The May version used a three-point turn maneuver as a shared timestamp anchor.

DiSogra claims methodologies changed in May’s supplemental report, and his PowerPoint incorporated those revisions.

📋 Scenarios and Variability

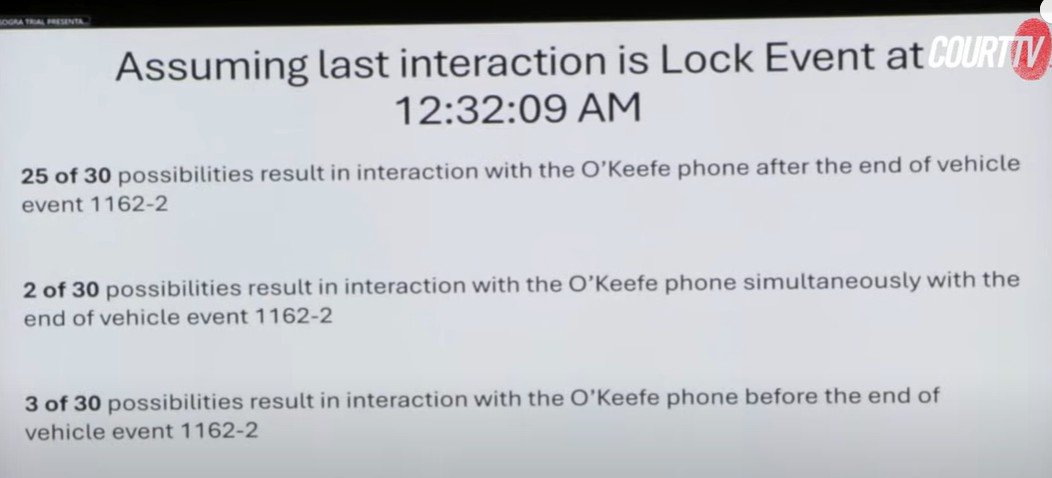

DiSogra identified 30 possible scenarios of phone lock timing vs. vehicle data:

- 27 scenarios: phone lock after the event

- 3 scenarios: phone lock before the event

- Some scenarios were simultaneous

- No best practice exists for aligning clocks without established standards, so all scenarios are equally weighted.

*** Critical Case Clue ***

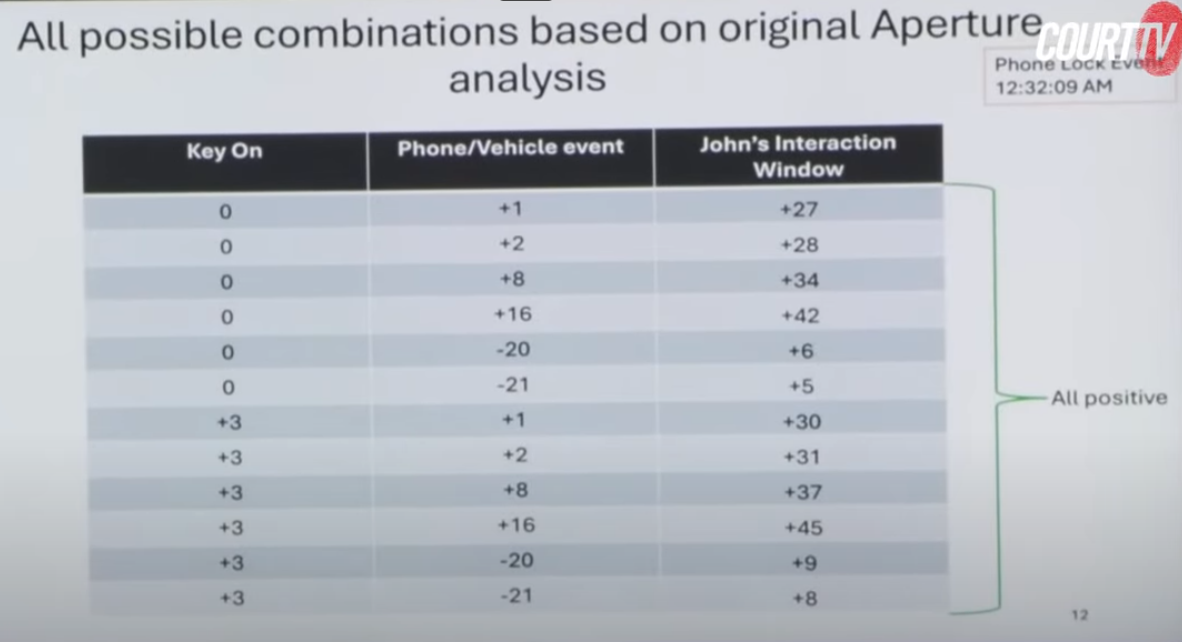

In the first image above, DiSogra states that his analysis is based on 30 possible scenarios. However, this is inaccurate. When all data points are accounted for—including the zero values shown in the second image—the actual number of possibilities rises to 36. Therefore, when DiSogra claims that “3 out of 30 possibilities result in interaction with the O’Keefe phone before the end of vehicle event 1162-2,” the statement is misleading. Including the zero values—representing instances where the phone lock occurred simultaneously with the vehicle event—yields 10 out of 36 scenarios in which John O’Keefe interacted with his phone before or at the same time as the event.

That is, of course, if we accept this methodology as valid in the first place.

One subtle but critical point—largely overlooked in the courtroom—was DiSogra’s challenge to Burgess’ choice to reference the end time of the event rather than the trigger point. We know that the trigger occurred when the accelerator was suddenly depressed to 75%, initiating a burst of acceleration that reached 24 mph. Yet, within the 10-second event window, there is no indication of braking—suggesting the vehicle was still in motion beyond the recorded frame.

This raises a pivotal question: even if the phone lock occurred after the event window closed, could the actual impact have taken place after that moment as well?

Given that the phone was ultimately discovered beneath O’Keefe’s body, it's reasonable to infer that he manually locked the device and placed it in his back pocket prior to the impact. Upon contact, the phone likely fell from his pocket and came to rest beneath him—where its battery temperature immediately began to drop, further supporting the idea that the final interaction preceded the collision.

❤️🩹 DiSogra Critiques Prosecution Witnesses Burgess and Welcher

DiSogra raised several concerns about the methodology used by both Burgess and Welcher. Regarding Burgess, he criticized the failure to test all possible offsets, including variations with and without the known three-second lag in the vehicle data. Burgess also neglected to conduct additional vehicle testing that could have validated or challenged his assumptions. DiSogra argued that a scientifically rigorous analysis would have explored a broader set of combinations and scenarios.

As for Dr. Welcher, DiSogra took issue with both his methodology and the presentation of his findings. He claimed that one of Welcher’s slides was misleading, particularly in its framing of the timeframe. Welcher referred to activity occurring “within 26 seconds” of the event, which DiSogra interpreted narrowly as “after” the incident—when, in fact, the data might have supported interactions that occurred before the event window closed. The critique seemed aimed less at the data itself and more at the clarity and objectivity of its interpretation.

😢 Cross Examination Drama

DiSogra’s cross-examination was, in a word, brutal. It became glaringly apparent that he had no formal training or experience in analyzing phone data. He admitted that he had performed no independent testing and had never analyzed the full dataset himself—instead relying on other experts’ reports. In particular, he relied on Burgess’s May report.

When pressed, DiSogra couldn’t explain why the vehicle’s infotainment system logs some calls but not others, nor how iPhones interact with that system—an alarming gap given the phone-centric nature of his testimony. In fact, DiSogra openly acknowledged that he has no expertise in iPhones whatsoever. His wheelhouse lies solely in TechStream data analysis, which significantly narrows the scope of his authority.

Perhaps most damaging was his omission of six entries in his analysis that bore simultaneous timestamps—data points that could potentially challenge his conclusion. As the cross-examination wore on, DiSogra appeared visibly flustered, frequently sighing, eye-rolling, and showing signs of irritation. Attorney Brennan, conducting the cross, did not let up—relentlessly pressing him on inconsistencies and highlighting the superficial depth of his analysis. By the end, it was clear that DiSogra’s confidence had taken a serious hit.

⚖️ Final Impressions

DiSogra presented himself as someone trying to be more precise, but undermined his own credibility by relying on secondhand data and failing to apply basic best practices (like testing multiple scenarios).

Admitted there’s no conclusive method to determine if the phone lock occurred before or after the vehicle event with certainty.

Yet, the overall takeaway is that in most scenarios, the phone lock happens after the vehicle event, which may help the defense with resonable doubt if the jury finds this witness more credible than the prosecution witnesses.

Related Articles

Related

Why Karen Read’s $1.4M Prosecution Expense Is Justified

When Norfolk County released invoices showing that Karen Read’s second trial cost taxpayers more than $1.4 million, critics pounced. But is that number really excessive? Not when you compare it with other high-profile, expert-heavy prosecutions. Here’s why the expense...

Suffolk County DA Responds: “Kelly Dever Not on Brady List”

Suffolk County DA Kevin Hayden | Image Credit: (Boston Globe)The fallout from Dever’s testimony in the Commonwealth v. Karen Read trial has sparked a new wave of outrage from Free Karen Read (FKR) supporters, even stating that Kelly Dever "already has a Brady file"....

Federal Grand Juror Leak in Karen Read Case | The Turtleboy Connection

Image Credit: (Nancy Lane/Boston Herald/File)“The Quiet Phase”: How the Karen Read Leak Strategy Unfolded—and What Comes Next While media and social chatter are focused on the recent indictment of juror Jessica M. Leslie, and her plea deal, the story’s real juju lies...